I’m involved in a project to create a virtual learning experience for law students this summer. Spurred by the pandemic and its impact on law students’ summer employment opportunities, a group of forward-thinking people came together to ask, how can we help students right now? What can we do, with what we have, where we are?

I’ll be sharing more on the project shortly.

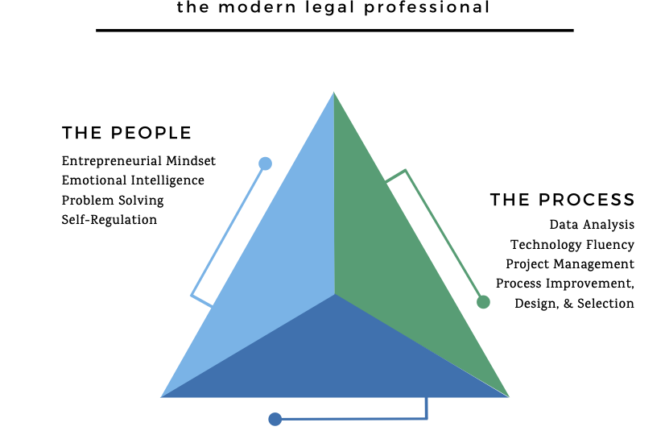

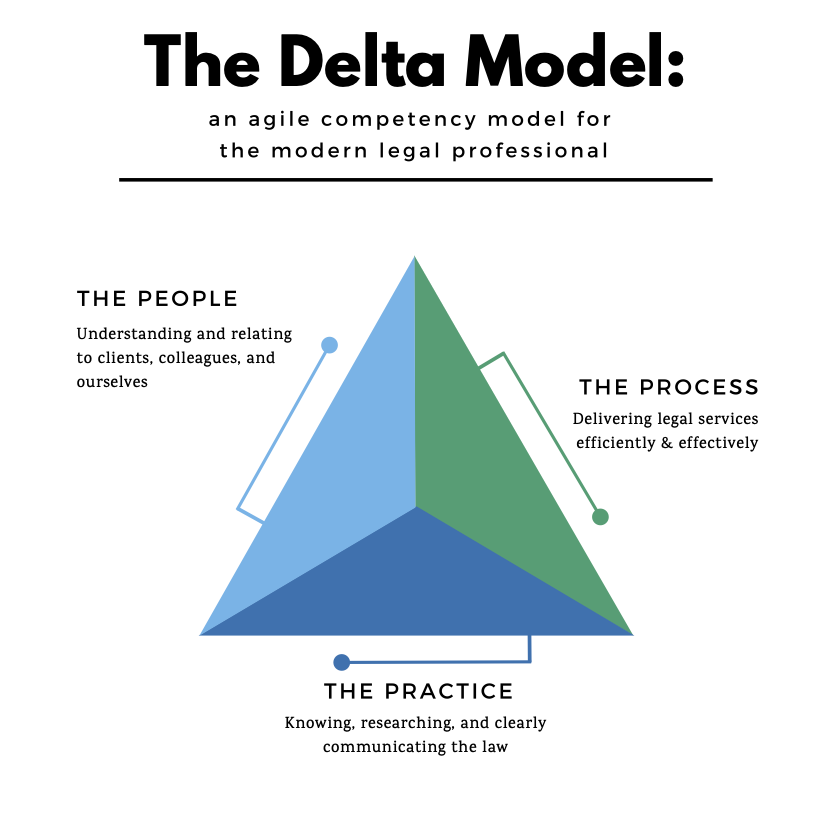

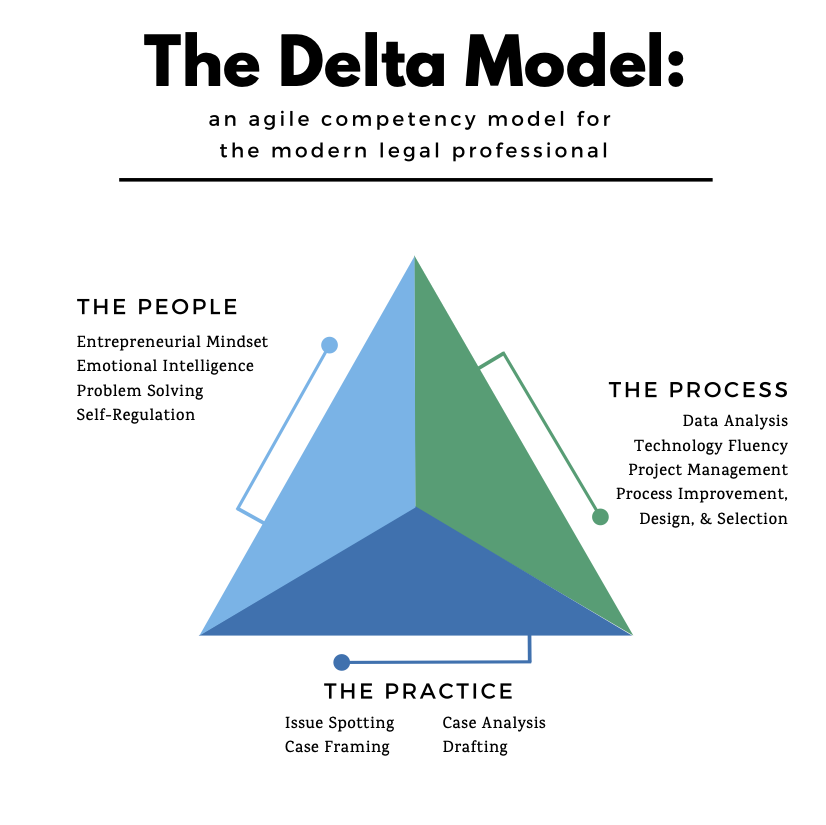

I mention it because the idea of a law students’ bill of rights came up in planning this learning experience. Our group is focused on giving students meaningful interaction with skills existing on the People and Process sides of the Delta Model. Skills that are largely absent from most law school curricula, and frankly don’t appear in many summer employment experiences, either. And, they’re critical to lawyer formation, professional success, and general thriving.

As we considered what we should be offering students, one of our group referenced a (yet to exist) law students’ bill of rights as a way to articulate what students should be getting out of their early formative learning experiences in law. (I use this phrase intentionally, to be broader than just law school.)

What do law students have a right to, from a legal education? And what comprises a legal education?

These feel like important questions to me. I think we’re going to explore them. With law students. Stay tuned.

And, if this is a topic of interest to you, let me know via Twitter.

-CM