I recently attended a by-invitation-only conclave convened to explore the future of legal services, from a global perspective. In the room? Legal educators, law company c-suite folks, operations counsel from global technology companies, leaders of legal for the Big 4, members of the current ABA Commission on the Future of Legal Education. An interesting mix of people, certainly.

Attendees were asked to contribute a short paper on one of three topics. Not surprisingly, I chose the topic “design principles for law school curricula in the light of future developments in the market for legal services.”

Here is what I submitted:

The very existence of this second Conference on the Future of Legal Services affirms that the legal profession rests on shifting sands. Accordingly, I will forgo a belabored review of what is changing, and by how much, and why. And I will simply point out that what lawyers do and how we do it looks very different today than it did when my grandfather entered the practice in the 1940s, and when my father entered the practice in the 1960s, and even when I entered the practice in the 1990s. The pace of this change is not going to slow, and most likely will continue to hasten.

If we accept this as true, then what is the import for legal

education? For surely, if what lawyers do and how we do it is changing, then

how we educate and train new lawyers should change. Many people have been

discussing this for quite a while. Consider Thomas D. Morgan’s proposal that

the ABA’s law school reform efforts in 2011 “must necessarily begin — at

least implicitly — with the question of what kind of people law schools are

charged with producing.”[1]

This question remains at the heart of any inquiry into legal education.

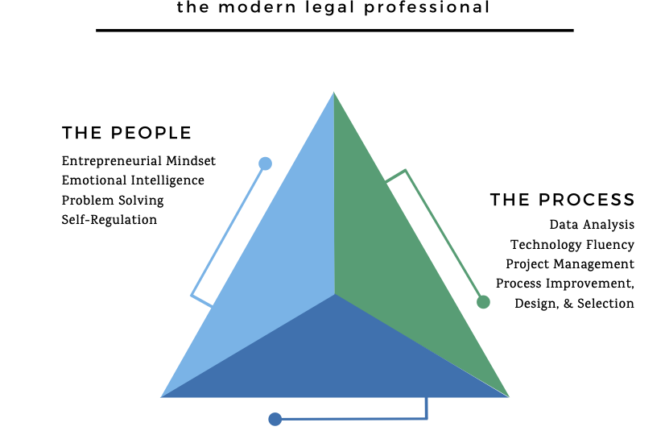

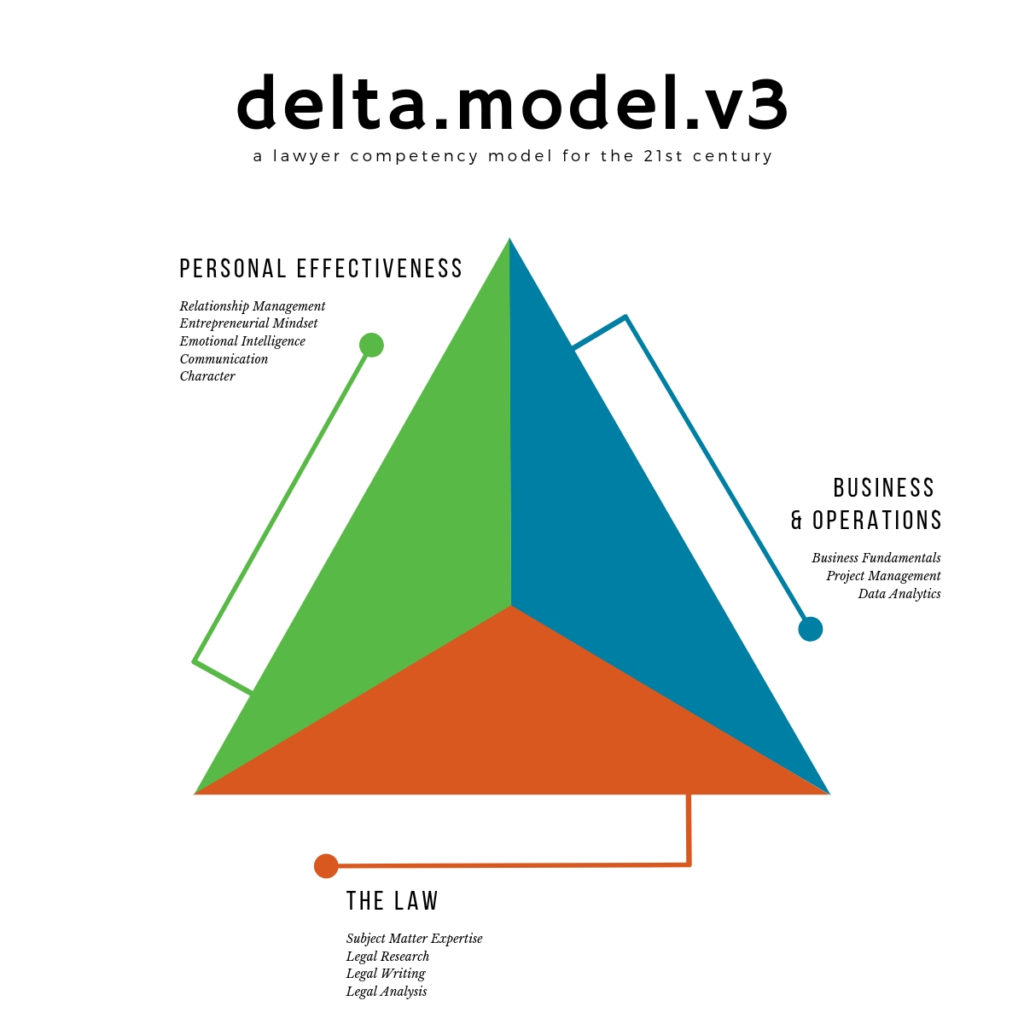

I recently joined the working group for the Delta Competency Model[2], which seeks to describe the core competencies required to be a successful modern legal practitioner: this is the kind of person law schools are charged to produce. Comprised of three primary competency areas — the law, personal effectiveness, and business and operations — the model offers an agile and dynamic framework for describing the skills and characteristics today and tomorrow’s lawyers — and legal professionals generally — need to thrive.

My proposal is simple: we need a new flavor of legal education with a curriculum designed to teach these competencies. This must happen in the immediate future, and it must be a path to both a legal practice (as a licensed lawyer) as well as positions that do not necessarily require bar passage and licensure, such as legal operations engineer, legal designer, legal process architect, and many more positions that will be needed and do not yet exist.

How do we do this? This also is very simple: the ABA creates a sandbox for designing and testing new flavors of accredited legal education, to include curricular content aligned with modern competencies (e.g. the Delta Model) and delivered using modern pedagogical best practices, including methods based in learning science and integrating advanced technology. All at a cost to law students that does not unduly burden them financially and therefore limit (or dictate) their reasonable employment options post-graduation.

Our obligations to uphold the rule of law and provide access to justice are too great for us to continue with our heads buried in these shifting sands. I’m a 5th-generation lawyer practicing for 20+ years. And I will leave legal education and the profession completely before I stand idly by and bear witness to our continued collective hubris. The time is now.

-CM

[1] Thomas D. Morgan, The Changing Face of Legal Education: Its Impact on What It Means to Be a Lawyer, 45 Akron L. Rev. 811, 811 (2011).

[2] The Delta Competency Model: see https://www.alysoncarrel.com/delta-competency-model